Gefundene Bücher

I went for a long walk through the neighborhood yesterday. I have a regular walk along the canals but decided to take off in a different direction, walk along some new (for me) streets and maybe find something interesting. I was keeping my eyes open for used bookstores (Antiquariate) and junk shops (Trödelläden) because you never know where you can find some interesting old paper (see my other blog posts here, here, and here, among others).

It turns out that one place to find old paper, or at least old books, is in Kungerkiez, a tiny neighborhood tucked between Alt-Treptow and Neukölln. It's not a Kiez I know well even though it's not far. What caught my eye as I was wandering, and where I found the books below, was an art gallery and used bookstore operated by the Kungerkiez Stadtteilzentrum, or local community center. The gallery is small, but with big windows and good light that shows the art quite well. After a quick look at the paintings (good, but maybe not remarkable) I started poking through the books. There weren't many but the section I was immediately drawn to, without knowing what it was, was the free book section - all the old and strange books deemed "un-sellable".

Ahhh...could there be a better section?

As it was my first visit, and as it's a donation-supported neighborhood non-profit (not to mention that I didn't have a backpack), I made a point of not being greedy. I found four books, but also kind of just two, as they're each two volumes in different series.

“...the old and strange books deemed ‘un-sellable’.”

Egon Friedell was a Viennese author, playwright, Kabarett performer, and cultural historian. He was a staple of the Viennese café scene and contemporary of Rainer Maria Rilke, Arthur Schnitzler, and Hugo Hofmannsthal.

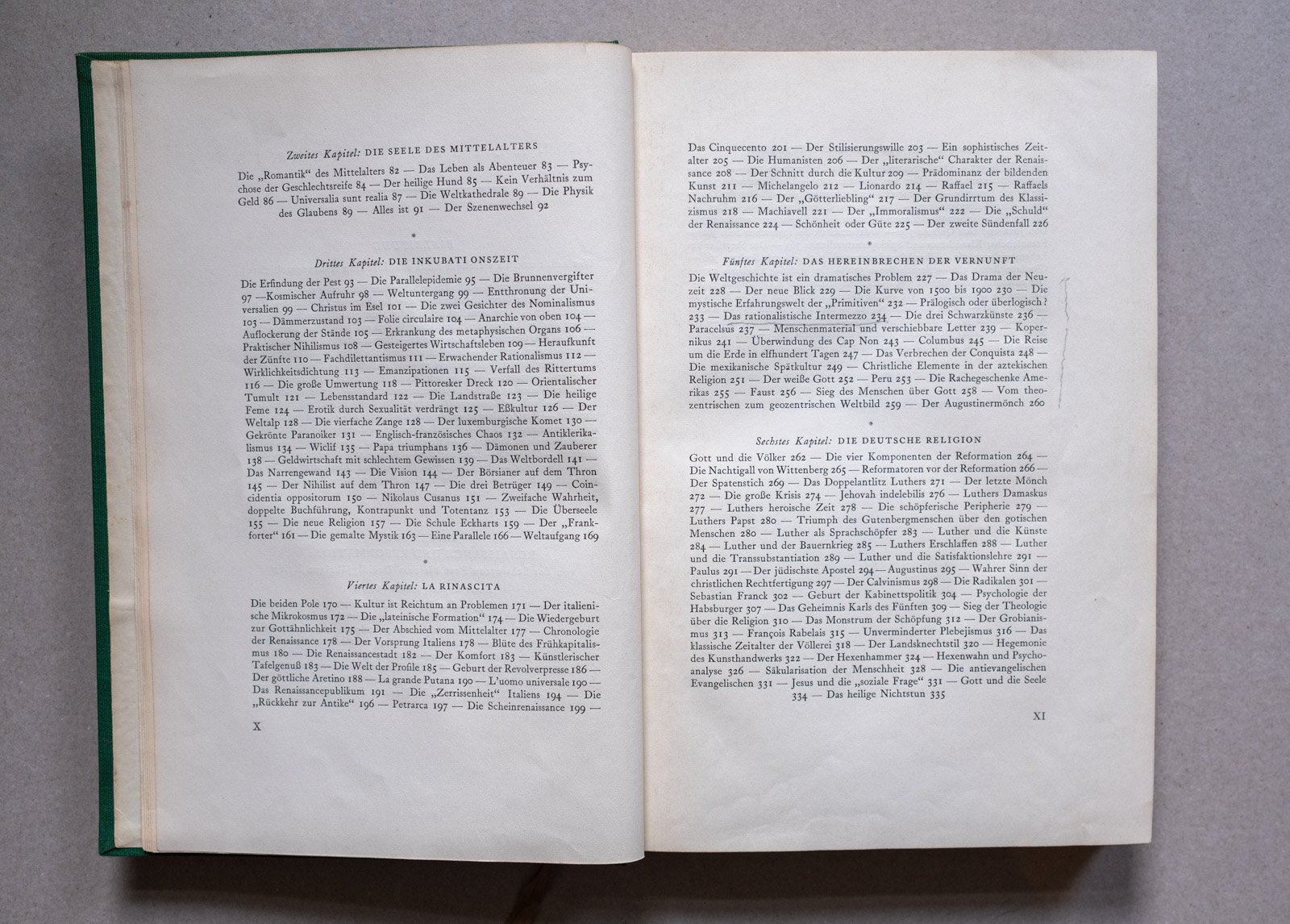

Between 1927 and 1931 he published his three-volume Kulturgeschichte der Neuzeit: Die Krisis der europäischen Seele von der Schwarzen Pest bis zum Weltkrieg (Cultural History of the Modern Age: the crisis of the European soul from the black death to the world war).

I found the first two volumes, Einleitung/Renaissance und Reformation, and Barock und Rokoko/Aufklarung und Revolution. At the time I had no idea there was a third. Now I have something to find, though I imagine it won't be too difficult.

“Translated into English in 1930, the three-volume set of his Cultural History of the Modern Age was such a publishing disaster that it simply vanished. Today it can be obtained only from a dealer in rare books. In the original German, however, Kulturgeschichte der Neuzeit turns up secondhand all over the world, because it was a talisman for the emigration: The refugees took it with them even though, in its usual three-volume format, it weighed more than a brick.”

The refugees mentioned above are the Austrian and German jews who were fortunate to leave before the rise of the Nazi party and the horrors of the concentration camps. Egon Friedell didn't leave. He committed suicide in 1938 as SA officers arrived to arrest him at his home.

I've not had any time to read it yet, but I may not have to. Orange 94, an independent Austrian radio station, broadcast the entire three volumes in 130 hour-long podcast episodes.

Felix Klein was a German mathematician active in the late 1800s and early 1900s, responsible for a bunch of seemingly impressive research work that I can't begin to understand. Relevant to this blog post, in his later career he became interested in mathematics education and published a number of lectures on elementary mathematics including Elementarmathematik vom höheren Standpunkte aus (Elementary mathematics from a higher point of view).

I found Teil 1: Arithmetik, Algebra, Analysis, and Teil 2: Geometrie. It's unclear if there are more volumes in this series or not, though Wikipedia shows several other lectures published through 1933 (posthumously).

What I love about these books is how they're printed from his handwritten notes. I don't know how these were printed, maybe some sort of lithography? Regardless, they look great. The print quality doesn't trick you into thinking it's actually his handwriting, but the pages are alive, and the illustrations are stellar. I can't read the handwriting to save my life but these pages could make stellar collage sources.

As I do with sources like this, I’m likely to sit on these for a while before I do anything with them. With over 1,000 pages of mathematics lectures alone, I have a good 500 sheets to play with but I still can’t allow myself to start cutting them up and printing on them until I’m a bit more familiar with them.

The geometry lecture came with a little bonus inside, a few sheets of folded A4 paper with handwritten notes, presumably on the contents of the book. The notes are dated 1947 and 1948 but without any biographical information that hints at their provenance.